The other day someone asked me, What are the premises of your book? I found the question most interesting, even provocative, as the nature of a premise is that it is a proposition from which another statement follows as a conclusion, usually taking two such premises.

First Principles

When the premise statement is not itself a conclusion from prior premises, then it is an assumption, a presupposition, a first principle. Every system known to mankind is built on unprovable presuppositions, as Kurt Gödel famously proved. (Sorry, I was an Applied Math major who studies cosmology on the side, and still nerd out on occasion. . . .)

Every system known to mankind is built on unprovable presuppositions

I’m actually influenced on first principles less by Isaac Newton and Kurt Gödel than by my friend and colleague Kim Korn, who coauthored Infinite Possibility with me. As he helped me with that book, I am helping him with his ideas (and eventual book) on Regenerative Managing, which shows how companies can avoid falling into mediocrity and then fail, and instead thrive forever. Regenerative Managing was not built on “argument by anecdote”, as Kim calls it – researching some class of companies that are great, agile, lasting, or whatever other topic thought important, and then finding their commonalities – but rather from the ground up based on first principles of humans organizing to create economic value, which logically makes for a much, much better argument.

The Transformation Economy Premises

The Transformation Economy – and in large measure prior works I’ve written – are based on first principles, where examples are used to illustrate the first principles, rather than to determine the first principles. (That is not to say that I do not develop principles from examples – just not first principles. Jim Gilmore and I use the phrase “data point of one” to indicate how even one company doing something innovative can yield a new principle from which other companies can benefit.)

So what are the premises of the new book? After thinking about it, I decided that these are my first principles:

At the top level of the Progression of Economic Value, transformations are a distinct economic offering.

The raison d’être of business is to foster human flourishing.

Although I can marshal a lot of evidence and even logic for both of these premises (see, not coincidentally, the first two chapters of the book when it comes out!), I cannot prove them.

But I know them to be true in my bones. And everything in The Transformation Economy: Guiding Customers to Achieve Their Aspirations flows from them.

I cannot prove them, but I know them to be true in my bones!

Transformations as a Distinct Economic Offering

There is a logic to the Progression of Economic Value, particular in how each successive economic offering is built on top of the one below, how they are economically distinct, satisfying distinctly different needs, generating distinctly different value, requiring distinctly different methods of creation, and charging customers in a distinctly different way. But it took until the late 18th century for economists to declare that services were a distinct economic offering. In fact, in The Wealth of Nations from 1776 – July 4th of that year, to be precise! – Adam Smith called those who worked in jobs other than commodity extraction and manufacturing “unproductive labourers”, and singled out those in experiences: “players, buffoons, musicians, opera-singers, opera-dancers, &c.”.

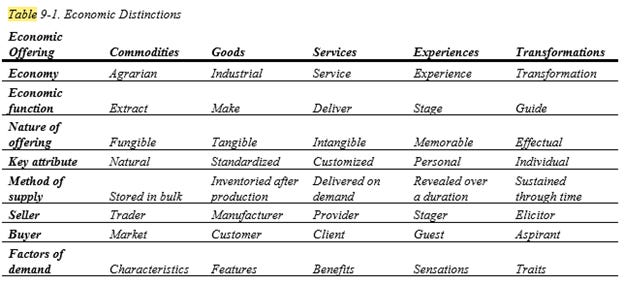

And I’m still waiting for mainstream economists to catch up to the Experience Economy much less transformations. (It just needs one person to champion it in the Bureau of Labor Statistics or its equivalent in other countries. Anyone know anyone???) But the distinctions are clear! Since the new book doesn’t list them in full, let me show here the table of economic distinctions from The Experience Economy (p. 224):

[You might notice one change I made in the new book: changing the seller of transformations to be a guider rather than an elicitor. It just seemed to make more sense in the writing.]

But is that proof? For me, its ideas harmoniously knitted together are good enough for me to make the claim of experiential and existential truth. But since that doesn’t seem good enough for everyone, I’ll call it my first premise: transformations are a distinct economic offering.

Human Flourishing as the Raison d’Être of Business

The second premise definitely has to be taken on faith. When it came to me in the writing – that the reason for existence for business was to foster human flourishing – it just felt right.

I originally planned a chapter on the four spheres of transformations at the end of which I would write about how they all overlapped and came together in human flourishing. Each one helped aspirants to flourish. It began as sort of a kicker – an extra little idea that was exciting, but not fully fleshed out.

And then I began fleshing it out.