Goods are inventoried after production, services are delivered on demand, and experiences – transformative experiences included – are revealed over a duration of time. [i] Experience design is the design of time, as I learned from the late famed architect, Jon Jerde,[ii] and dramatic structure shows how the complication or intensity of an experience changes over time – rising up to a climax and coming back down again – and thus do experiences become memorable.

In The Experience Economy, Jim Gilmore and I describe a number of ways to think about dramatic structure.[iii] Most notably we introduced seven stages of the famed Freytag Diagram (taught in most every theatre class), which I love to use to analyze and design experiences of all stripes.[iv] Then we tell of the 5E model that originated with the Doblin Group (now a Deloitte Business) and alliterated by Kathleen Macdonald, one of our Certified Experience Economy Experts: Enticing, Entering, Engaging, Existing, Extending.[v] This generally proves much easier for businesses to use (certainly to remember).

We further discuss two three-stage models, the first one being the simple structure of a story: beginning, middle, and end. Then there’s the Imagineering model of The Walt Disney company: pre-show, show, post-show, which like the 5Es recognizes that experiences begin before guests actually take in “the show” and that they can and should be extended through time. And finally there’s the one-stage model: signature moment, the climax of the experience where you create something bordering on spectacular that is so famous that guests expect it, look forward to it, and enjoy it immensely. Think of the end-of-day parade at Disney theme parks or the throwing of fish at the Pike Place Fish Market.

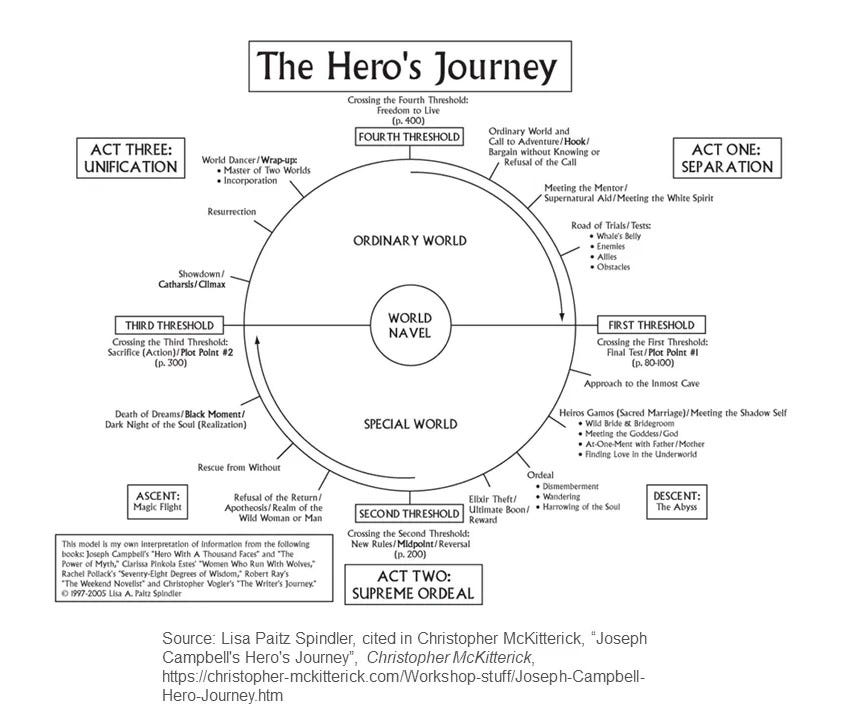

One dramatic structure framework we did not discuss there is the Hero’s Journey,

discovered and delineated by Joseph Campbell in his seminal book The Hero with a Thousand Faces.[vi] What’s most interesting about this framework – elucidated through Campbell’s reading and study of mythologies – is that it’s not only a dramatic journey, it’s a transformational journey. It describes how a seemingly ordinary person (or hobbit), living a normal life, encounters something very unexpected (what Gustav Freytag called “the inciting incident”), which sets him off on a journey into the unknown. He leaves his ordinary world into a “special world” where he confronts dangers, is helped and guided by a wise old man/wizard/Jedi.[vii] He faces the threat of death (if not death itself, as with Harry Potter), and eventually saves the world/Middle-Earth/Galaxy far, far away. Finally, our hero returns to his ordinary world, transformed.

There are many differing representations of the Hero’s Journey that vary from eight to Campbell’s original 17 stages. The one I like best was created by writer and content strategist Lisa Paitz Spindler and is shown here.[viii] As the note in the drawing indicates (which you’ll likely only be able to read by seeing it online, unfortunately) shows that she drew not only from Campbell’s work but other sources as well, and I think it provides a rich tapestry of thinking through the many possibilities in this twelve-stage model of dramatic transformation structure.

Make Your Customers Heroes

Think now about making your customers into the heroes of their own transformational journeys.